MALI : Self-determination or recolonization ?

toni solo, 22 de mayo 2012

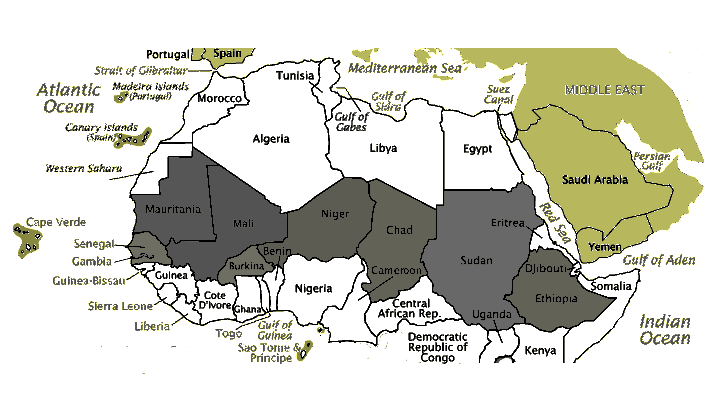

In this map of northern Africa, the Sahel countries are shaded

Mali is a country sharing borders with Algeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Guinea, Senegal and Mauritania. Its natural resources are coveted by the oligarchies that control North America and Europe. Following the recent military coup that enjoyed widespread popular support, the people of Mali are caught between the hostile economic choke hold of NATO's West African proxies and successful armed insurgencies by Islamic extremists and the Tuareg ethnic group.

The nationalist aspirations of the Tuareg have been manipulated by foreign governments and politicians to undermine Mali's territorial integrity. Islamic extremists in Mali are backed by NATO's allies in the feudal tyrannies of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States and have been directly supplied by Qatar by air at the northern Mali city of Gao. These ethnic and Islamic insurgencies have brought chaos to northern and central Mali.

Thousands of people have been killed and around three hundred thousand people have been displaced. The chaos intensified after the March 22nd military coup against the corrupt, ineffectual Malian government in Bamako, the country's capital. The insurgencies threaten Mali's territorial integrity and also the stability of North Africa's main regional power, Algeria.

The background to the complexities of events in Mali since March 22nd 2012 has been the implacable, endless war on humanity waged by the European and North American oligarchies. Their power is in decline relative to powerful competitors like China and Russia. To prolong their centuries old international dominance and access to raw materials and energy resources, the North American and European élites have destroyed one vulnerable nation state after another.

The people of Mali are the victims of this deep geopolitical logic. They have suffered directly from NATO's destruction of Libya. That colonialist aggression gave Islamic and ethnic insurgent forces in northern Mali ready access to vast amounts of high quality weapons and well-maintained munitions. Both Mali and its neighbours have also been badly affected by the return of many hundreds of thousands of black African migrant workers who fled Libya during the war or were expelled by Libya's racist CNT regime.

Following the coup of March 22nd, the people of Mali have suffered economic sanctions applied by the neocolonial stooges who control the Economic Community of West African States (1). ECOWAS leaders have acted with extreme hypocrisy on behalf of their former colonial masters, France and Britain. The genocidal terrorist governments of those countries, the United States and their NATO accomplices have trashed international law, but still use the empty shell that remains against any country that resists their will.

What has happened in Mali makes no sense unless seen in the geopolitical context of neocolonial terrorist aggression by the NATO powers and their allies. The scale of that military and economic aggression is global, reaching from the Korean Peninsula, to the South China Sea, through Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and Syria, through Somalia, Sudan and Libya, to Mali and its neighbours and across the Atlantic to Latin America. Their mineral wealth and oil and gas reserves make Mali, Niger and Algeria targets for yet another neocolonial NATO intervention.

History

By its history and geography, Mali has always been central to political and economic developments in West Africa. The empires of Ghana, Mali and Songhai were based largely on control of trade routes crossing the Sahara. The cities of Jenna and Timbuktu in what is now the Republic of Mali were important cultural and commercial centres for many centuries.

During Africa's colonial conquest by the European powers in the 19th century, France attacked and took control of vast areas of North and West Africa. In 1905, Mali was incorporated into the French empire as French Sudan and remained so for over fifty years. Around the same time that France was forced to concede independence to Algeria, Mali, jointly with Senegal, became independent in 1960 as the Mali Federation within the so called French Community of former French colonies.

Senegal withdrew from the federation almost immediately to become an independent state. Mali's government, led by the socialist Modibo Keita, declared a republic at the end of 1960 and withdrew from the French Community. In 1968, Modibo Keita's government was overthrown by a coup led by Moussa Traoré who held power for over 20 years until 1991.

In that year, widespread protests began on March 22nd against endemic poverty and corruption. Traoré's government repressed the protests, killing hundreds. On March 26th 1991, General Amadou Toumani Touré led a successful military coup that allowed elections in 1992 won by Alpha Oumar Konaré. Prior to the fall of the Traoré regime, longstanding dissent and resistance among the Tuareg population of northern Mali turned into armed conflict, leading to vicious repression by the Malian army.

That conflict was resolved only after bitter fighting and mediation which led to a peace agreement in 1995. A less widespread conflict broke out in 2006 which was also resolved by a peace agreement. The Tuareg are a largely nomadic people that for centuries have inhabited a huge area of the Sahara covering parts of what are now Algeria, Burkina Faso, Libya, Mali and Niger.

In 2002, Amadou Toumani Touré was elected President of Mali. Following re-election, he held office until March 2012. His government came to be regarded as increasingly corrupt and incompetent, failing in particular to defend Mali's territorial integrity against resurgent Tuareg nationalism. Early in 2012 Tuareg nationalist forces, greatly strengthened militarily following their participation in the Libyan war, took up again their historic grievances against the Malian government by forming the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad.

They joined forces with the militia of former Malian ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Tuareg chief Iyad Ag Ghali. This militia took the name of the already well-established Malian Islamic charitable and community development organization Ançar Dine. These Tuareg forces, in loose coordination with the salafist Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQMI), attacked poorly equipped and demoralised Malian army units across northern Mali, rapidly taking control of large areas.

The coup and subsequent events

On March 22nd, an emblematic day in Mali's history, a group of junior officers led by Captain Amadou Haya Sanogo organized a coup as the National Committee for the Return of Democracy and the Restoration of the State (NCRDRS). Their move to depose President Amadou Toumani Touré had high levels of popular support. But they quickly found their coup itself challenged by Mali's neighbours in the ECOWAS and by the African Union.

Within Mali, the coup was largely welcomed by the Malian people, despite coming just a month prior to new elections. The great majority wanted the changes necessary to address relentless poverty, growing unemployment, declining provision for education and health care, corrupt use of public funds and the deepening collapse of government authority. Above all they supported the coup as a means of moving quickly to reaffirm Mali's territorial integrity.

The NCRDRS initially proposed a national consultative process to fix a date for elections and to discuss how Mali should change. But within days of the successful coup, Mali was faced with financial and commercial sanctions applied by ECOWAS. Regional hostility to the coup in Mali is the latest expression of the way NATO's corrupt and repressive local allies in Africa work to impose regional compliance with Western demands.

The severe economic sanctions imposed by ECOWAS worked in favour of the United Front to Save Democracy and the Republic (FUSADER), a group of Mali's political class and civil society who had done well under President Touré's government. They and ECOWAS pressed for a return to normality under the 1992 Constitution.

An agreement was reached on April 6th 2012, naming the head of Mali's National Assembly as interim President with the task of organizing new elections within 40 days. All through April, the ECOWAS leadership under Ivory Coast President Alassane Ouatarra maintained the suggestion of a force of 3000 ECOWAS soldiers to help “stabilize” the situation in Mali. That apparent offer of help against the northern insurgencies was self-evidently a threat of military intervention against the NCRDRS leadership.

While Captain Sanogo and his colleagues negotiated with ECOWAS mediator President Compaoré of Burkina Faso, the situation in northern Mali worsened. Tuareg and Islamic insurgents captured major towns like Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu. On April 6th the Tuareg National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad representative Mossa Ag Attaher announced a new State called Azawad covering most of north and central Mali – around 60% of Mali's national territory.

Preoccupied by the economic aggression, political hostility and potential threat of an ECOWAS military intervention, the authorities in Mali were unable to organize a military campaign to retake national territory. By the end of April, relations between the NCRDRS and the interim President Dioncounda Traoré, effectively imposed by ECOWAS, had deteriorated badly. Dioncounda Traoré resisted continuing efforts by Captain Sanogo and his CNRDRS colleagues to organize a national convention, in effect a constituent assembly, for the Malian people to decide how they want their country to be governed.

ECOWAS used its ability to damage Mali's economy so as to renege on the terms of the April 6th agreement. At a meeting in Abidjan on April 26th, ECOWAS unilaterally tried to impose a 12 month transition period that blatantly favoured their Malian allies in FUSADER. The ECOWAS manoeuvre was vigorously rejected by the CNRDRS whose leaders were determined to avoid a return to the kind of government the coup had been intended to end for good.

On April 30th an attempted counter coup by paratroops loyal to former President Touré was quickly suppressed by the Malian army. The counter coup was a gross miscalculation by ECOWAS leaders like President Ouatarra of Ivory Coast and President Compaoré of Burkina Faso. Along with the renegade paratroopers, Ivory Coast militia members were also detained.

The counter coup demonstrated beyond doubt that ECOWAS would exploit any movement north of troops by Mali's interim authorities by helping reactionary anti-coup forces take control in Mali's capital Bamako. All through May 2012, the CNRDRS was under pressure from ECOWAS. Captain Sanogo and his colleagues were forced to choose between achieving their hoped for political change in Mali or being able to undertake a military campaign to recover lost national territory.

That reality led the CNRDRS to accept the imposition by ECOWAS of an interim presidency of twelve months for Dioncounda Traoré. In exchange, ECOWAS appeared to guarantee support for an offensive by the Malian army to retake territory currently held by the northern insurgent groups. But at the same time Captain Sanogo and his colleagues went ahead with the organization of a national convention to discuss Mali's political future. The ECOWAS imposed deal provoked mass protest demonstrations in Bamako demanding interim President Traoré's resignation.

West African context

The ECOWAS countries that have taken the lead in challenging the popular change of regime in Mali are its neighbours Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso. President Alassane Ouatarra of the Ivory Coast was installed in power by the helicopter gunships and heavy weaponry of French and United Nations troops who helped Ouatarra's genocidal militias depose the legitimate government of Laurent Gbagbo in 2011. The UN and France engineered the coup to oust President Gbagbo simultaneously with NATO's campaign of mass terror to destroy Libya and murder Muammar Al Ghaddafi.

The confluence of NATO neocolonial aggression in North and West Africa follows a familiar pattern. Like Ivory Coast President Ouatarra, Burkina Faso's President Blaise Compaoré is also a sinister enforcer for the NATO powers. Compaoré came to power in 1987 by betraying and murdering legendary revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara. Ouatarra and Compaoré are determined defenders of NATO country interests, especially French interests, in West Africa.

Their role is the same as that of ruthless repressive leaders like Paul Kagame of Rwanda and Yowere Museveni in Uganda. They defend NATO country corporate interests in Africa against the expansion of Chinese trade and investment interests. Like Kagame and Museveni, ECOWAS leaders are totally subordinate to NATO's plutocrat oligarchies.

Mali and its ECOWAS neighbours are all victims of the aid and debt development model used by the NATO powers to keep former colonies in neocolonial economic and political subjugation. That model requires the compliance of a corrupt, repressive local political elite and the suppression of mass political mobilization by the impoverished majority. That is why the ECOWAS Western puppets have moved so decisively to roll back the overthrow of their corrupt counterparts in Mali.

ECOWAS was supported by the full weight of the NATO countries' neocolonial system. Mali is helplessly integrated into a financial and economic system dominated by French financial interests and by international financial institutions like the World Bank and the IMF. It is part of the West African Economic and Monetary Union. Its currency is the Franc of the African Financial Community (CFA Franc) whose convertibility is controlled by the French Treasury.

The CFA Franc is issued by the Central Bank of West African States which is part of the Western financial system, dominated by the countries of North America and the European Union. This economic and financial dependence on the NATO powers is vital to Western control of the region's natural resources. Its political importance is clear from the way the NCRDRS leaders in Mali have been forced to accept the demands of ECOWAS and its NATO masters.

Recolonization

Other complexities abound. Algeria views with great suspicion the French government's undisguised desire to get unrestricted use of the Malian military air base at Tessalit near the Algerian border, ostensibly for operations against terrorist groups and organized crime. Algeria's leaders, like other African leaders, may come to regret the passive role they took in relation both to NATO's aggression against Libya and NATO country manipulation of the secession of Southern Sudan.

Surrounded now by unsympathetic or downright hostile governments and extremist Islamic movements, Algeria can hardly welcome the collapse of central authority in Mali. On May 20th it announced it was sending 3000 tons of rice to help parts of Mali's population suffering food shortages. Algerian diplomats have been kidnapped in northern Mali by the AQMI offshoot, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa. That group has clashed with the Algerian army while attempting to hijack petrol tankers and has also kidnapped foreign aid workers.

AQMI itself has strong roots in the Algerian Islamic extremist groups that destabilized Algeria through the 1990s, the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) and the Salafist Proselytizing and Combat Group (GSPC). In 2010, Algeria, Mali, Niger and Mauritania formed the Joint High Command Operational Centre (CEMOC) to address the perceived threats from organized crime and Islamic armed groups. It is far from clear that Algeria can count on support from NATO countries despite all their propaganda about the “war on terrror” and the “war on drugs”.

Those slogans are little more than light make-up over what is in fact a global war on humanity by the North American and European élites. NATO allies Saudi Arabia and Qatar provided crucial support in the destruction of Libya. Now they actively support the armed Islamic groups in the Sahel in general and in Mali in particular. They would like to see hard line Islamic governments take over secular countries like Algeria and moderate Islamic countries like Mauritania.

Mauritania's current leader Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz seems to be playing off Tuareg national aspirations against the threat posed by Islamic extremists. The governments of Saharan countries like Mauritania are challenged by AQMI, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa and even elements of the extremist Nigerian Islamic movement Boko Haram. Mauritanian forces have made several unauthorized incursions into Mali in pursuit of these armed Islamic groups.

Up to a point, Mauritania's President Abdel Aziz seems to be supporting French and United States policy in the region, undermining the sovereignty of Mali. The NATO powers have shown in Lebanon, Libya and Syria that they will work closely with Islamic extremists if it suits their neocolonial agenda. They do so either directly as they did in Afghanistan in the 1980s or, as they have done more recently, in alliance with the feudal tyrannies of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States who have directly supported terrorism against the peoples of Lebanon, Libya and Syria.

The double-game played by the NATO powers in relation to Islamic extremist movements is matched by their hypocrisy in addressing organized crime and narcotics in the region. Narcotics, people trafficking and contraband of all kinds are lucrative multinational businesses generating hundreds of billions of dollars a year. That money flows into the Western financial system propping up its virtually insolvent major banks, as even the relevant UN organization has acknowledged.

At the same time, organized crime and narcotics justify high levels of spending for the Western armament and security industries. So the North American and European governments have a double interest. They falsely claim to defend democracy and human rights and act against terrorism and organized crime. In practice, they sadistically destroy countries and peoples so as to advance their geopolitical interests and stem the decline of their global power and influence.

Similarities to Central America

The events around the coup in Mali and its regional context have many characteristics in common with Central America. The country and the region are impoverished, geopolitically important and vulnerable to destabilization. The colonial and post colonial history of the region has left countries like Mali humiliatingly dependent on the former colonial powers.

Local oligarchies exploit the futile trappings of electoral democracy to ensure their own power and privilege. They work to subordinate their peoples' interests to those of the criminal, genocidal, terrorist Western oligarchies. A superficial analysis of the coup in Mali might liken it to the coup in Honduras in June 2009. Such a comparison would be completely false.

The widely supported coup in Mali is the logical response to a failed government system too weak even to defend its own territory. Captain Sanogo and his NCRDRS colleagues have clearly stated they want no foreign troops on their territory and have repeatedly insisted on the need for a national convention to reform the Malian Republic. They have done so in the face of opposition from Mali's dominant elite and that elite's foreign backers in ECOWAS and the NATO countries.

By contrast, the coup in Honduras was carried out by a reactionary oligarchy determined to defend their elite interests and those of the United States. They have welcomed new US military bases on their territory and ruthlessly suppressed mass popular demonstrations calling for a constituent assembly. Since the coup, social indicators in Honduras have worsened dramatically leaving it with one of the highest murder rates in the world.

In contrast to the norm in West Africa and Central America, one country in Central America has been able to prise loose the dead hand of North American and European dominance. Nicaragua joined the Bolivarian Alliance of the Americas (ALBA ) in 2007 and has made rapid social and economic progress thanks in great measure to support from Venezuela and Cuba. The NATO oligarchies detest Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua because those countries have created an economic model independent of the West's neocolonial model of aid and debt.

NATO destroyed Libya partly because it wanted free access to Libya's oil but also because Muammar Al Ghaddafi was playing a similar role in Africa to that of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez in Latin America and the Caribbean. When popular unrest erupts as it has done in Mali, the criminal NATO elites are haunted both by the ghosts of legendary revolutionaries like Thomas Sankara and by contemporary revolutionaries like Fidel and Raul Castro, Hugo Chávez and Daniel Ortega.

NATO's vile murder of Muammar al Ghaddafi and the UN coup against President Laurent Gbagbo removed key regional voices for progress and stability. The result for the people of Mali will be prolonged conflict and suffering under the constant threat of intervention by the ECOWAS nations or their NATO masters. Mali is now another country living the horrific consequences of the West's global war on humanity.

Malian writer and former Minister of Culture Aminata Traoré puts the situation succinctly :

“The US and European crisis has an answer in the wealth of Africa. As in Ivory Coast and Libya, they have activated a diplomatic and media offensive to justify intervention. It's time for our peoples to be as politically lucid and decisive as they were in the era of national liberation, so as to cut our losses and if possible set ourselves free. If one considers the media coverage granted the MNLA and its rhetoric one can understand that France is using them to return again to its former colonies.”

Note

1. The fifteen West African States that constitute ECOWAS are Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Ivory Coast, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo.